Baseball clearly needs a salary cap. I wouldn't say that the Twins are cheap. In my opinion there are some really ridiculous contracts out there especially in all sports in general.Cheap ownership and "the Twins way" of handling pitchers make it real, real hard to have any faith in this team next season.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

All Things 2021 Minnesota Twins In-Season Thread

- Thread starter BleedGopher

- Start date

forever a gopher

Well-known member

- Joined

- Nov 20, 2008

- Messages

- 3,455

- Reaction score

- 3,511

- Points

- 113

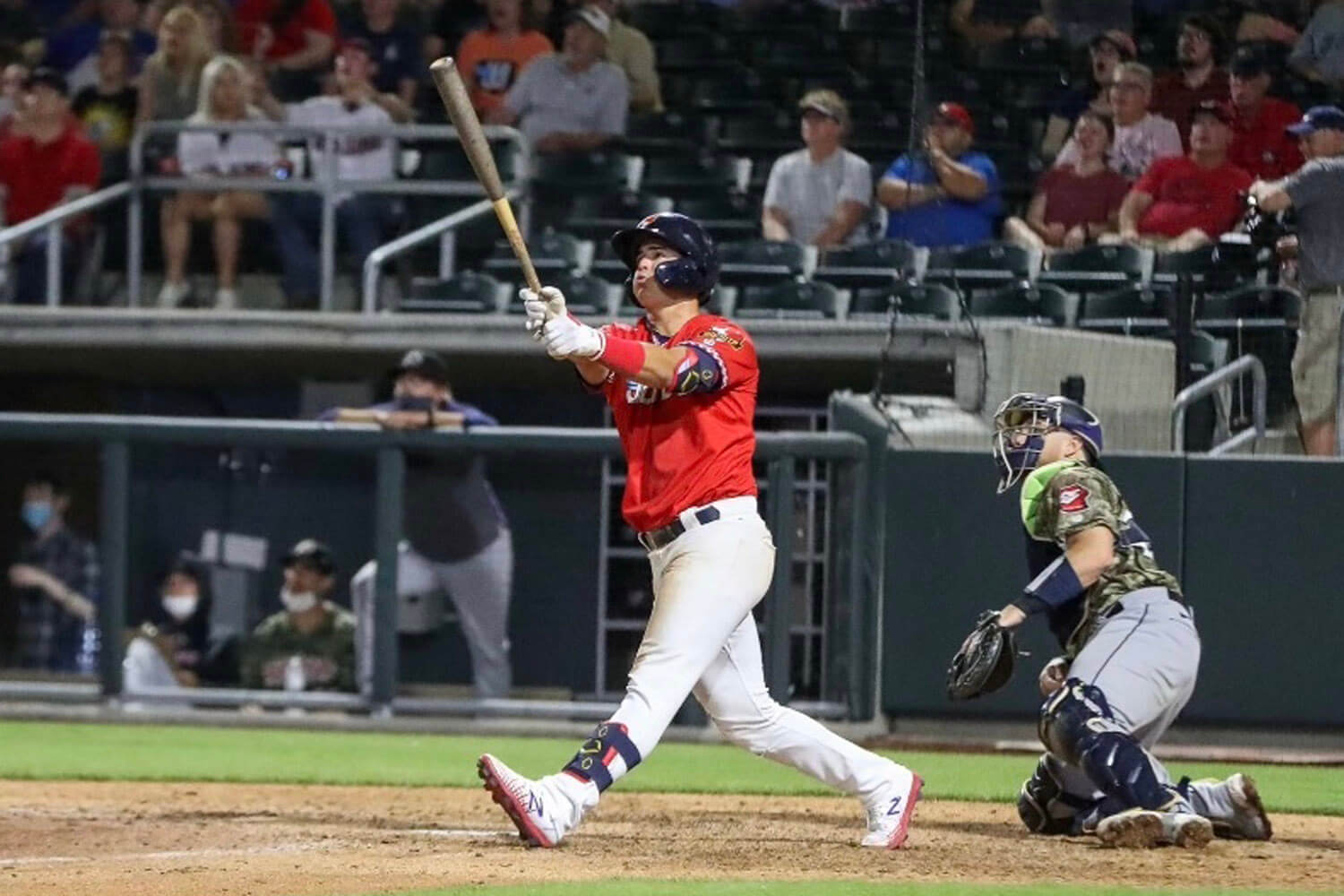

Saw him at the Saints game last week. Was excited to see him, and of course he goes 1/5 with 3k's. I was a bit skeptical of the Saints getting in bed with the Twins and how that might affect their "wacky" brand. I will say, it's pretty cool to be able to see the farm system so easily.Is it for real? Jose Miranda is having the best season by a Twins hitting prospect in 20 years

Is it for real? Jose Miranda is having the best season by a Twins hitting prospect in 20 years

Unprotected and unpicked in the Rule 5 draft, Miranda is now forcing his way into the Twins' plans with a breakout season.theathletic.com

Eight months ago, the Twins left Jose Miranda unprotected from the Rule 5 draft and the 23-year-old infielder was not selected by any of the 29 other MLB teams, remaining in the organization without requiring a spot on the 40-man roster.

Miranda was a decent prospect, ranking No. 30 on my Twins top-40 list this spring and No. 39 in 2020, but the 2016 second-round pick had yet to convert his oft-praised raw hitting tools into notable production in the minor leagues. He hit a combined .258/.315/.395 in his first four pro seasons, including just .248/.299/.364 with eight homers in 118 games at High A in 2019.

Like most other prospects, Miranda missed out on seeing any game action in 2020 because COVID-19 wiped away the minor league season. But he put in work behind the scenes with Twins coaches, who encouraged the free-swinger to take a more disciplined approach at the plate in an effort to avoid putting so many out-of-zone pitches in play and get Miranda into more hitter’s counts.

“He has such good feel for the barrel, it almost didn’t matter what the pitcher threw,” Twins player development director Alex Hassan said. “He was going to be aggressive because he knew he could hit the ball. We challenged him to be more selective early in the count. Let’s try to narrow your strike zone early in the count and look to do more damage.”

In other words, they wanted Miranda to stop letting pitchers off easy just because he had the contact skills to put nearly any pitch in play. While that aggressive approach led to few strikeouts because he rarely went deep in counts, it also generated few walks and underwhelming overall production from a hitter with far too much natural talent to be slugging below .400.

The change in approach has worked in ways the Twins could never have imagined as Miranda has put together one of the biggest breakout seasons in all of minor league baseball. It started at Double A, where Miranda batted .345/.408/.588 with 13 homers in 47 games. That earned him a promotion to Triple A, where he’s been even better, hitting .354/.415/.654 with nine homers in 30 games.

Combined between the two levels, Miranda is hitting .349/.411/.614 with 22 homers and 19 doubles in 77 games while striking out just 49 times versus 30 walks in 360 plate appearances. He led the Double-A Central league in OPS at the time of his promotion and now has the second-best OPS in the Triple-A East league.

Miranda, a right-handed batter, is hitting .330 versus righties and .392 versus lefties. He’s posted an OPS above .950 in every month. And he’s done it while facing pitchers older than him in 92.8 percent of his plate appearances, hitting .360 off them. Miranda has multiple hits in 33 of 77 games, including a pair of five-hit games, one of which was his three-homer Triple-A debut on June 29.

Not only is Miranda having the best 2021 season of any Twins minor leaguer and one of the best 2021 seasons by any prospect, period, he’s on track for the highest OPS by a Twins prospect in the past 20 years. Better yet, the company Miranda is keeping suggests that having this type of monster season in the high minors is an extremely good sign for a prospect’s future.

Here are the highest OPS numbers posted by 23-and-under Twins prospects playing at Double A or Triple A in the past 20 years (minimum 300 plate appearances):

Only five 23-and-under Twins prospects playing in the high minors have come within 100 points of Miranda’s current OPS in the past 20 years, and all five of them went on to become good, and occasionally great, regulars for the Twins.

PROSPECT YEAR AGE PA OPS Jason Kubel 2004 22 549 1.004 Justin Morneau 2004 23 326 .992 Miguel Sanó 2013 20 519 .992 Michael Cuddyer 2002 23 372 .973 Max Kepler 2015 22 508 .930 Jose Miranda 2021 23 360 1.025

Also of note is that, unlike those five prospects, all of whom ended up as corner outfielders or first basemen, Miranda has a chance to stick as a second baseman or third baseman (or perhaps a super-utility man who also dabbles at shortstop and first base). He’s played all four infield spots this season, with his most action at second and third, where Twins officials consider him average or better.

Jason Kubel, Justin Morneau, Miguel Sanó, Michael Cuddyer and Max Kepler were established as top prospects with impressive track records when they put up those big numbers in the high minors, whereas Miranda’s high-minors breakout is occurring after four mostly underwhelming seasons. However, he’s long been touted as a potential breakout candidate by Twins officials and what he’s doing this season is truly special.

Miranda has added 100 points to his batting average and tapped into massive power while upping his walk rate and barely sacrificing the contact skills that were his primary calling card prior to 2021. Compared to his last season, 2019, his isolated power is up 130 percent and his walk rate is up 70 percent, yet his strikeout rate has only risen from 11.2 percent to a still-low 13.6 percent.

“He’s always been really hard to strike out, with incredible bat-to-ball skills,” Hassan said. “Now we’re starting to see that profile come together, where he’s driving the ball and he’s still maintaining that incredible bat-to-ball skill.”

To do that while jumping from High A to Double A, and then quickly Triple A, following a cancelled season is incredibly promising, and within the context of the past two decades of Twins prospects it’s all but unheard of for anyone not destined to become a first baseman or corner outfielder. So yes, there’s reason to be skeptical of Miranda’s star potential, but there’s also reason to buy in.

If the Twins were to trade Josh Donaldson this offseason, Miranda could take over at third base. In the unlikely event the Twins move Jorge Polanco back to shortstop following Andrelton Simmons’ impending departure as a free agent, Miranda could take over at second base. And if the Twins keep Donaldson and Polanco in place, Miranda could still factor into the 2022 plans as a utility man.

And the way he’s playing, we might even see him at Target Field in 2021.

Gopher_In_NYC

Well-known member

- Joined

- Apr 19, 2010

- Messages

- 24,934

- Reaction score

- 17,327

- Points

- 113

Sorry you didn't see his debut with the three bombs.Saw him at the Saints game last week. Was excited to see him, and of course he goes 1/5 with 3k's. I was a bit skeptical of the Saints getting in bed with the Twins and how that might affect their "wacky" brand. I will say, it's pretty cool to be able to see the farm system so easily.

How did he look in the field?

forever a gopher

Well-known member

- Joined

- Nov 20, 2008

- Messages

- 3,455

- Reaction score

- 3,511

- Points

- 113

There weren't any plays that required him to be exceptional or make a splashy play. But nothing I saw made me think he's a liability or looked out of place at second.Sorry you didn't see his debut with the three bombs.

How did he look in the field?

Baseball does need a cap.Baseball clearly needs a salary cap. I wouldn't say that the Twins are cheap. In my opinion there are some really ridiculous contracts out there especially in all sports in general.

But the Twins haven't been "cheap" for the most part since moving out of the Dome. They've just made some really dumb decisions. This off-season they were interested in Marcus Semien and Brad Hand but instead chose to sign Simmons, Colome, JA Happ and Shoemaker. The amount spent was the same. To say nothing of sacrificing LaMont Wade and Akil Badoo to keep freaking Jake Cave around.

Ope3

Sailor Sam

- Joined

- Dec 12, 2008

- Messages

- 13,783

- Reaction score

- 10,604

- Points

- 113

I went to the Indy/Saints game last Friday. Miranda was flat out awful at 2B. He booted a routine grounder which led to a big inning and misplayed a throw from the catcher on a steal. Hopefully, small sample size.

It was my first Saints game since the move from Midway. I enjoyed it and prefer the affiliation with the Twins. Prices are pretty close to level with MLB though, once in the stadium. It's not a bargain at all compared to Target Field.

It was my first Saints game since the move from Midway. I enjoyed it and prefer the affiliation with the Twins. Prices are pretty close to level with MLB though, once in the stadium. It's not a bargain at all compared to Target Field.

Gopher_In_NYC

Well-known member

- Joined

- Apr 19, 2010

- Messages

- 24,934

- Reaction score

- 17,327

- Points

- 113

I wonder if 3rd will be where he ends up eventually.I went to the Indy/Saints game last Friday. Miranda was flat out awful at 2B. He booted a routine grounder which led to a big inning and misplayed a throw from the catcher on a steal. Hopefully, small sample size.

It was my first Saints game since the move from Midway. I enjoyed it and prefer the affiliation with the Twins. Prices are pretty close to level with MLB though, once in the stadium. It's not a bargain at all compared to Target Field.

I guess Rocco's software update worked?Crazy, after going winless in their first 7 extra inning games, after tonight they are now 7-9 when going past the scheduled amount.

boofbonser

Well-known member

- Joined

- Nov 30, 2014

- Messages

- 606

- Reaction score

- 648

- Points

- 93

That’s always the position most mentioned with him. They need to have a replacement for Donaldson ready next year or the year after so it would make the most sense.I wonder if 3rd will be where he ends up eventually.

Donaldson has been gimping around for a week. IL him already and get Miranda up here.That’s always the position most mentioned with him. They need to have a replacement for Donaldson ready next year or the year after so it would make the most sense.

Gopher_In_NYC

Well-known member

- Joined

- Apr 19, 2010

- Messages

- 24,934

- Reaction score

- 17,327

- Points

- 113

Good article from LaVelle on this clown move -

www.startribune.com

www.startribune.com

OUSTON - Nelson Cruz, Jose Berrios, J.A. Happ and Hansel Robles were dealt before the trade deadline, netting the Twins seven prospects, six of them pitchers.

It's standard procedure for a team that was never in contention despite a roster that was designed to win a third consecutive AL Central title. President of Baseball Operations Derek Falvey and General Manager Thad Levine don't sit on the fence at the deadline. Since their hiring before the 2017 season, the duo has made 17 July deals — with 2020 not counting because the season was just beginning because of the pandemic.

Falvey and Levine, however, could have done more this deadline. A couple of players who should be elsewhere were on the field for the Twins on Saturday during a 4-0 loss to the Astros.

Righthanded starter Michael Pineda and shortstop Andrelton Simmons are both approaching free agency. There were some health concerns about Pineda since he recently came off the injured list, which apparently affected his market.

We're going to focus on Simmons, who made a nice stop to his right in the second inning on Saturday but could not get a throw off as the first run of the game scored.

Houston took a 2-0 lead on Yordan Alvarez's home run in the fourth. The Astros added two runs in theeighth off of Caleb Thielbar, and that was all. Pineda went six solid innings, but Josh Donaldson and Luis Arraez didn't start because of injuries. The Twins ended up with a four-hit attack.

Simmons, 0-2 with a strikeout before being lifted for a pinch hitter in the eighth, has not delivered on the $10.5 million contract he signed during the offseason and should have been traded for whatever the club could have received for him.

BOXSCORE: Houston 4, Twins 0

According to a source, there wasn't a strong market for Simmons so no progress was made toward a deal. His continued presence doesn't aid the quest to improve in 2022.

He was asked to be the great defensive player he's been throughout his career — actually, he's arguably the best defensive shortstop of his generation — while mentoring other infielders, particularly top prospect Royce Lewis. Any offense was a plus, and it allowed Jorge Polanco to shift to second base, where he has thrived.

Simmons, 31, has been more good than great with the glove. He committed an error during his Twins debut on Opening Day and has eight overall. His Defensive Runs Saved is six, which puts him in the top five. But the man has had a rating of 30 or more three other times in his career.

He's never been known for his hitting skills, but his .220 batting average would be a career low. That'scoming off a 2020 season during which he batted .294. The substitution in the eighth was pure strategy.

"We were just trying to get a baserunner," said manager Rocco Baldelli of sending Arraez and his sore left knee to hit for Simmons.

Simmons' mentoring of Lewis ended when the prospect needed season-ending knee surgery in the spring. Simmons apparently has done fine work with Polanco and the current stable of infielders. That once included Nick Gordon, which is another problem.

The Twins sent Gordon to Class AAA St. Paul on Thursday, presumably to get plenty of at-bats while playing all over the field. Twins officials express optimism that Gordon will be back this season. But September callupshave changed. Rosters can be expanded from 26 to just 28, not up to 40 anymore. And the Saints' season ends Oct. 3, not Labor Day.

I'd rather see Gordon — who's 25 and finally healthy after fightingintestinal issues and COVID in recent years — develop with the Twins than watching a lame duck Simmons. Simmons should have been moved before the deadline.

And the Twins will have another bridge-to-Lewis problem next season — or a bridge to Austin Martin, a shortstop who came in a package from Toronto for Jose Berrios.

So be prepared next spring to greet the new Opening Day stopgap shortstop: Freddy Galvis.

Why is Andrelton Simmons still with the Twins?

Why is Andrelton Simmons still with the Twins?

The shortstop is the sort of player who should have been dealt by now given his team's failure and his production.

OUSTON - Nelson Cruz, Jose Berrios, J.A. Happ and Hansel Robles were dealt before the trade deadline, netting the Twins seven prospects, six of them pitchers.

It's standard procedure for a team that was never in contention despite a roster that was designed to win a third consecutive AL Central title. President of Baseball Operations Derek Falvey and General Manager Thad Levine don't sit on the fence at the deadline. Since their hiring before the 2017 season, the duo has made 17 July deals — with 2020 not counting because the season was just beginning because of the pandemic.

Falvey and Levine, however, could have done more this deadline. A couple of players who should be elsewhere were on the field for the Twins on Saturday during a 4-0 loss to the Astros.

Righthanded starter Michael Pineda and shortstop Andrelton Simmons are both approaching free agency. There were some health concerns about Pineda since he recently came off the injured list, which apparently affected his market.

We're going to focus on Simmons, who made a nice stop to his right in the second inning on Saturday but could not get a throw off as the first run of the game scored.

Houston took a 2-0 lead on Yordan Alvarez's home run in the fourth. The Astros added two runs in theeighth off of Caleb Thielbar, and that was all. Pineda went six solid innings, but Josh Donaldson and Luis Arraez didn't start because of injuries. The Twins ended up with a four-hit attack.

Simmons, 0-2 with a strikeout before being lifted for a pinch hitter in the eighth, has not delivered on the $10.5 million contract he signed during the offseason and should have been traded for whatever the club could have received for him.

BOXSCORE: Houston 4, Twins 0

According to a source, there wasn't a strong market for Simmons so no progress was made toward a deal. His continued presence doesn't aid the quest to improve in 2022.

He was asked to be the great defensive player he's been throughout his career — actually, he's arguably the best defensive shortstop of his generation — while mentoring other infielders, particularly top prospect Royce Lewis. Any offense was a plus, and it allowed Jorge Polanco to shift to second base, where he has thrived.

Simmons, 31, has been more good than great with the glove. He committed an error during his Twins debut on Opening Day and has eight overall. His Defensive Runs Saved is six, which puts him in the top five. But the man has had a rating of 30 or more three other times in his career.

He's never been known for his hitting skills, but his .220 batting average would be a career low. That'scoming off a 2020 season during which he batted .294. The substitution in the eighth was pure strategy.

"We were just trying to get a baserunner," said manager Rocco Baldelli of sending Arraez and his sore left knee to hit for Simmons.

Simmons' mentoring of Lewis ended when the prospect needed season-ending knee surgery in the spring. Simmons apparently has done fine work with Polanco and the current stable of infielders. That once included Nick Gordon, which is another problem.

The Twins sent Gordon to Class AAA St. Paul on Thursday, presumably to get plenty of at-bats while playing all over the field. Twins officials express optimism that Gordon will be back this season. But September callupshave changed. Rosters can be expanded from 26 to just 28, not up to 40 anymore. And the Saints' season ends Oct. 3, not Labor Day.

I'd rather see Gordon — who's 25 and finally healthy after fightingintestinal issues and COVID in recent years — develop with the Twins than watching a lame duck Simmons. Simmons should have been moved before the deadline.

And the Twins will have another bridge-to-Lewis problem next season — or a bridge to Austin Martin, a shortstop who came in a package from Toronto for Jose Berrios.

So be prepared next spring to greet the new Opening Day stopgap shortstop: Freddy Galvis.

Gopher_In_NYC

Well-known member

- Joined

- Apr 19, 2010

- Messages

- 24,934

- Reaction score

- 17,327

- Points

- 113

Interesting article on The Athletic on what progress to watch for in the Twins rookies for the rest of the season this was written before Gordon got sent down again - ridiculous move.

theathletic.com

theathletic.com

At the beginning of the season, the Twins were one of the league’s oldest teams, led by 41-year-old Nelson Cruz. They expected to contend for a third straight AL Central title and spent the offseason filling in gaps with veteran free agents, leading to 13 of the 26 players on the Opening Day roster being 30 or older. To say that plan went poorly would be an understatement.

Many of their veterans struggled, with the free-agent signings of J.A. Happ (38 years old), Matt Shoemaker (34) and Alexander Colomé (32) especially dragging the team down. Never-ending injuries forced the Twins to dip into the minors for help, calling up several top prospects well ahead of schedule. They weren’t able to get back on track, eventually trading away a handful of key veterans.

And suddenly the Twins are no longer very old. They’re also not very good, but there’s a big difference between losing with one of the league’s oldest teams and taking your lumps with a rookie-filled roster gaining on-the-job experience, at least in terms of attempting to find some silver linings, and future value, within the losses. If you’re going to be bad, at least be young.

With that in mind, here are six Twins rookies with something to prove over the final two months and which storylines to keep an eye on to track their progress.

He’s hit .185 with 51 strikeouts in his past 33 games, dropping his OPS from .811 on June 20 to .676 today. On a related note: Larnach has seen the third-fewest fastballs in baseball, ahead of only noted fastball destroyers Jorge Soler and Shohei Ohtani. When he does get a rare fastball, he’s hit .301 with a .531 slugging percentage. When he doesn’t get a fastball, he’s hit .156.

It’s becoming increasingly common for young hitters to see an avalanche of breaking balls and changeups, as veteran pitchers waste no time putting them to the test in a way minor-league pitchers aren’t always capable of doing. This isn’t unique to Larnach — it was true of Alex Kirilloff before his season-ending wrist injury — but certainly he’s seeing even fewer fastballs than most rookies.

The good news is there are a couple of surefire ways to get pitchers to throw more fastballs. The bad news is they’re both a lot easier said than done. Larnach can start hitting off-speed pitches much better, in which case pitchers will dial back on them. Or he can start laying off more borderline off-speed pitches, forcing pitchers into fastball counts. That’s the challenge he faces down the stretch.

Rooker was recalled from Triple A to replace Cruz on the roster and has been the Twins’ primary designated hitter since, also seeing some action in left field. He’s already hit three mammoth homers since rejoining the team, but Rooker’s raw power has never really been in question. He has 38 homers in 530 at-bats between Triple A and the majors, most of them absolutely crushed.

What threatens to hold Rooker back are his high strikeout rates, low batting averages and limited defensive aptitude. He’s a career .260 hitter at Triple A, including .239 this season, striking out 175 times in 126 total games. And the bar for Rooker’s offensive production is higher than most because he’s a poor corner outfielder and a mediocre first baseman best suited for the designated-hitter role.

This season across the league, the average DH has hit .243/.320/.447 with 25 homers per 500 at-bats. That’s the baseline for Rooker warranting an everyday job. He’s hit .260/.380/.540 at Triple A, which certainly suggests he’s capable of at least matching those leaguewide numbers, but unless he gets the chance to prove it the Twins will never know for sure. He should get the chance now.

When he was posting video-game-like numbers in the minors despite the “soft tosser” label attached, Ober pounded the strike zone and relied heavily on off-speed pitches. It’s been a different story with the Twins so far. His control has been good but not great, with 2.7 walks per nine innings and a league-average strike rate, and Ober’s non-fastballs have gotten clobbered.

Opponents have slugged above .650 on Ober’s slider, curveball and changeup, with eight of his 11 homers allowed coming on off-speed pitches. Meanwhile, his fastball, once a high-80s question mark, is now a low-90s weapon. Thrown about 60 percent of the time, at an average of 92 mph, his fastball misses more bats than expected and has rarely been hit hard.

In particular, Ober has been able to take advantage of the additional perceived velocity that comes with his height by working up in the zone with his fastball, where it seems to surprise hitters by how quickly it gets on them. He’s ridden his improved fastball to 51 strikeouts in 47 innings, but the next step for Ober will be rediscovering his off-speed effectiveness against big-league bats.

Those two skills are more than enough to keep Jeffers in the majors for a long time, as catchers who can hit the ball over the fence at the plate and maximize called strikes behind it are in high demand. However, the rest of Jeffers’ game has been somewhat lacking so far, with two specific areas of improvement needed if he’s going to become an asset as the Twins’ long-term starter.

Stolen bases are less of a factor than ever across baseball, but Jeffers’ throwing was enough of an issue early that some teams game-planned challenging him. When the Twins demoted Jeffers to the minors in late April, he’d thrown out 14 percent of steal attempts for his career. Throwing mechanics became a point of emphasis, and since returning in early June he’s thrown out 34 percent.

Jeffers also made adjustments to his approach at the plate while in the minors and the results have been noticeable, but he continues to strike out a lot. That’s part of the equation for a power hitter, of course, but he’s whiffed in 34 percent of his plate appearances and hasn’t drawn the walks required to balance those out. He hasn’t chased a ton but has swung through too many pitches in the zone.

Lefties have hit .275 with a .571 slugging percentage off Alcala for his career, including six homers in 57 at-bats this season. He’s been great versus righties, holding them to .221/.258/.315 with the fastball-slider combo, but he lacks a dependable weapon versus lefties because Alcala’s changeup remains a work in progress at age 26.

At the urging of Twins coaches, Alcala has used his changeup more often of late, throwing it 16 percent of the time in June and July compared with just 8 percent in April and May. However, he’s yet to find consistency with the pitch, often forcing him to turn back to his fastball in key spots. That predictability is part of why he’s served up so many backbreaking homers.

It’s easy to see that Alcala should be an MLB-caliber reliever and perhaps even a late-inning asset. He throws very hard and has a breaking ball that generates swings and misses consistently against righties, but unless or until he can figure out a way to neutralize lefties at least somewhat, his upside will remain mostly theoretical. He has two months to work on his changeup.

Gordon has batted .247/.295/.326 in 35 games for the Twins, underwhelming production in line with his .255/.304/.368 mark in 177 games at Triple A. He’s a skinny slap hitter, as shown by eight homers in 791 at-bats between Triple A and the majors, yet Gordon strikes out a lot and rarely walks. That combo isn’t a recipe for hitting success, which is why Gordon’s versatility and speed are keys.

Gordon was drafted as a shortstop, but by the time he got to Triple A in 2018, he was splitting reps at shortstop and second base. He’s yet to receive a start at shortstop with the Twins and the bulk of his action has come in center field, a position he’d never played before two months ago. There have been predictable growing pains, but for the most part, Gordon has looked passable in center.

Fielding flexibility is essential to Gordon’s odds of sticking in the majors, with the Twins or elsewhere. He’s a marginal hitter and stretched at shortstop, but if he can be a reasonable emergency option there in addition to being playable at second base and center field — and maybe third base and the outfield corners eventually — that would go a long way toward finding him a niche.

Six key Twins rookies with something to prove down the stretch and how to track their progress

Six key Twins rookies with something to prove down the stretch and how to track their progress

Trevor Larnach, Brent Rooker, Bailey Ober, Ryan Jeffers, Jorge Alcala and Nick Gordon all have questions to answer in the final two months.

At the beginning of the season, the Twins were one of the league’s oldest teams, led by 41-year-old Nelson Cruz. They expected to contend for a third straight AL Central title and spent the offseason filling in gaps with veteran free agents, leading to 13 of the 26 players on the Opening Day roster being 30 or older. To say that plan went poorly would be an understatement.

Many of their veterans struggled, with the free-agent signings of J.A. Happ (38 years old), Matt Shoemaker (34) and Alexander Colomé (32) especially dragging the team down. Never-ending injuries forced the Twins to dip into the minors for help, calling up several top prospects well ahead of schedule. They weren’t able to get back on track, eventually trading away a handful of key veterans.

And suddenly the Twins are no longer very old. They’re also not very good, but there’s a big difference between losing with one of the league’s oldest teams and taking your lumps with a rookie-filled roster gaining on-the-job experience, at least in terms of attempting to find some silver linings, and future value, within the losses. If you’re going to be bad, at least be young.

With that in mind, here are six Twins rookies with something to prove over the final two months and which storylines to keep an eye on to track their progress.

Trevor Larnach: Ability to adjust

Larnach, the Twins’ preseason No. 3 prospect, made his debut at least a few months earlier than planned because of a steady stream of injuries to the big-league lineup. He got off to a strong start by hitting .267/.380/.431 in his first 37 games, showing impressive raw power and plate discipline for a rookie, but opposing pitchers have basically stopped throwing Larnach fastballs and he’s in a prolonged slump.He’s hit .185 with 51 strikeouts in his past 33 games, dropping his OPS from .811 on June 20 to .676 today. On a related note: Larnach has seen the third-fewest fastballs in baseball, ahead of only noted fastball destroyers Jorge Soler and Shohei Ohtani. When he does get a rare fastball, he’s hit .301 with a .531 slugging percentage. When he doesn’t get a fastball, he’s hit .156.

It’s becoming increasingly common for young hitters to see an avalanche of breaking balls and changeups, as veteran pitchers waste no time putting them to the test in a way minor-league pitchers aren’t always capable of doing. This isn’t unique to Larnach — it was true of Alex Kirilloff before his season-ending wrist injury — but certainly he’s seeing even fewer fastballs than most rookies.

The good news is there are a couple of surefire ways to get pitchers to throw more fastballs. The bad news is they’re both a lot easier said than done. Larnach can start hitting off-speed pitches much better, in which case pitchers will dial back on them. Or he can start laying off more borderline off-speed pitches, forcing pitchers into fastball counts. That’s the challenge he faces down the stretch.

Brent Rooker: Power and playing time

While still technically a prospect because he has fewer than 130 career at-bats in the majors, Rooker is 26 years old and has shown repeatedly that he can beat up on Triple-A pitching. What he hasn’t shown, mostly because he hasn’t gotten the opportunity yet, is that he can be a productive regular in the major leagues. That figures to change after Cruz’s trade to Tampa Bay.Rooker was recalled from Triple A to replace Cruz on the roster and has been the Twins’ primary designated hitter since, also seeing some action in left field. He’s already hit three mammoth homers since rejoining the team, but Rooker’s raw power has never really been in question. He has 38 homers in 530 at-bats between Triple A and the majors, most of them absolutely crushed.

What threatens to hold Rooker back are his high strikeout rates, low batting averages and limited defensive aptitude. He’s a career .260 hitter at Triple A, including .239 this season, striking out 175 times in 126 total games. And the bar for Rooker’s offensive production is higher than most because he’s a poor corner outfielder and a mediocre first baseman best suited for the designated-hitter role.

This season across the league, the average DH has hit .243/.320/.447 with 25 homers per 500 at-bats. That’s the baseline for Rooker warranting an everyday job. He’s hit .260/.380/.540 at Triple A, which certainly suggests he’s capable of at least matching those leaguewide numbers, but unless he gets the chance to prove it the Twins will never know for sure. He should get the chance now.

Bailey Ober: Off-speed pitches

For a team in desperate need of future rotation help, Ober’s emergence has been one of the few pitching bright spots of 2021. He worked behind the scenes in 2020 to get into better shape and add velocity to his fastball, and the results have been undeniably encouraging. He now throws 91-93 mph instead of 88-90, and the 6-foot-9 right-hander now looks like a building block.When he was posting video-game-like numbers in the minors despite the “soft tosser” label attached, Ober pounded the strike zone and relied heavily on off-speed pitches. It’s been a different story with the Twins so far. His control has been good but not great, with 2.7 walks per nine innings and a league-average strike rate, and Ober’s non-fastballs have gotten clobbered.

Opponents have slugged above .650 on Ober’s slider, curveball and changeup, with eight of his 11 homers allowed coming on off-speed pitches. Meanwhile, his fastball, once a high-80s question mark, is now a low-90s weapon. Thrown about 60 percent of the time, at an average of 92 mph, his fastball misses more bats than expected and has rarely been hit hard.

In particular, Ober has been able to take advantage of the additional perceived velocity that comes with his height by working up in the zone with his fastball, where it seems to surprise hitters by how quickly it gets on them. He’s ridden his improved fastball to 51 strikeouts in 47 innings, but the next step for Ober will be rediscovering his off-speed effectiveness against big-league bats.

Ryan Jeffers: Arm and contact

Jeffers has shown two clearly above-average skills since debuting for the Twins last August: power hitting and pitch framing. He has 12 homers in 206 at-bats, most of them no-doubters, so it’s easy to see the 6-4, 240-pound catcher’s strength on display. He’s also done a very good job getting called strikes for his pitchers, ranking 13th among all catchers in pitch framing since last season.Those two skills are more than enough to keep Jeffers in the majors for a long time, as catchers who can hit the ball over the fence at the plate and maximize called strikes behind it are in high demand. However, the rest of Jeffers’ game has been somewhat lacking so far, with two specific areas of improvement needed if he’s going to become an asset as the Twins’ long-term starter.

Stolen bases are less of a factor than ever across baseball, but Jeffers’ throwing was enough of an issue early that some teams game-planned challenging him. When the Twins demoted Jeffers to the minors in late April, he’d thrown out 14 percent of steal attempts for his career. Throwing mechanics became a point of emphasis, and since returning in early June he’s thrown out 34 percent.

Jeffers also made adjustments to his approach at the plate while in the minors and the results have been noticeable, but he continues to strike out a lot. That’s part of the equation for a power hitter, of course, but he’s whiffed in 34 percent of his plate appearances and hasn’t drawn the walks required to balance those out. He hasn’t chased a ton but has swung through too many pitches in the zone.

Jorge Alcala: Matchups versus lefties

Alcala’s stuff is too good for his performance to be this bad. He has a high-90s fastball and a sharp, bat-missing slider, yet his ERA is 5.27 ERA and he’s been unreliable in anything other than low-leverage relief situations. His biggest problem is the same one that caused the Twins to give up on him as a starter and move him to the bullpen in late 2019: Alcala can’t get left-handed hitters out.Lefties have hit .275 with a .571 slugging percentage off Alcala for his career, including six homers in 57 at-bats this season. He’s been great versus righties, holding them to .221/.258/.315 with the fastball-slider combo, but he lacks a dependable weapon versus lefties because Alcala’s changeup remains a work in progress at age 26.

At the urging of Twins coaches, Alcala has used his changeup more often of late, throwing it 16 percent of the time in June and July compared with just 8 percent in April and May. However, he’s yet to find consistency with the pitch, often forcing him to turn back to his fastball in key spots. That predictability is part of why he’s served up so many backbreaking homers.

It’s easy to see that Alcala should be an MLB-caliber reliever and perhaps even a late-inning asset. He throws very hard and has a breaking ball that generates swings and misses consistently against righties, but unless or until he can figure out a way to neutralize lefties at least somewhat, his upside will remain mostly theoretical. He has two months to work on his changeup.

Nick Gordon: Versatility

Several seasons filled with injuries and health problems, including a harrowing experience with COVID-19, nearly knocked Gordon off the prospect map, but the 2014 No. 5 pick fought his way back and reached the big leagues in May, seven years after the Twins drafted him. Now the question is whether or not he can convince the Twins he has the skill set required for a long-term bench role.Gordon has batted .247/.295/.326 in 35 games for the Twins, underwhelming production in line with his .255/.304/.368 mark in 177 games at Triple A. He’s a skinny slap hitter, as shown by eight homers in 791 at-bats between Triple A and the majors, yet Gordon strikes out a lot and rarely walks. That combo isn’t a recipe for hitting success, which is why Gordon’s versatility and speed are keys.

Gordon was drafted as a shortstop, but by the time he got to Triple A in 2018, he was splitting reps at shortstop and second base. He’s yet to receive a start at shortstop with the Twins and the bulk of his action has come in center field, a position he’d never played before two months ago. There have been predictable growing pains, but for the most part, Gordon has looked passable in center.

Fielding flexibility is essential to Gordon’s odds of sticking in the majors, with the Twins or elsewhere. He’s a marginal hitter and stretched at shortstop, but if he can be a reasonable emergency option there in addition to being playable at second base and center field — and maybe third base and the outfield corners eventually — that would go a long way toward finding him a niche.

GophersInIowa

Well-known member

- Joined

- Nov 21, 2008

- Messages

- 46,915

- Reaction score

- 31,433

- Points

- 113

It’s time. Let Gordon and Polanco take over for the next two months.

TruthSeeker

Well-known member

- Joined

- Nov 8, 2014

- Messages

- 7,911

- Reaction score

- 4,585

- Points

- 113

We already know the answer. Polanco cannot play SS. He's a 2B.

Ope3

Sailor Sam

- Joined

- Dec 12, 2008

- Messages

- 13,783

- Reaction score

- 10,604

- Points

- 113

Alcada's ERA is lower than Maeda's (5.03 before tonight).

Big game tonight in the race to finish in 3rd place. Really odd they play Detroit in 8 straight.

I think the battle for 3rd place is over with the Twinks now 5 games behind the Tigers. May the 4th be with them, though they are 2 games behind the Royals in the loss column.

TruthSeeker

Well-known member

- Joined

- Nov 8, 2014

- Messages

- 7,911

- Reaction score

- 4,585

- Points

- 113

Might as well get 5th. They'll want a better draft position.I think the battle for 3rd place is over with the Twinks now 5 games behind the Tigers. May the 4th be with them, though they are 2 games behind the Royals in the loss column.

It's especially important this year because they're not playing next year. That means there won't be a draft, so the 2023 draft should be especially deep.

Ope3

Sailor Sam

- Joined

- Dec 12, 2008

- Messages

- 13,783

- Reaction score

- 10,604

- Points

- 113

Might as well get 5th. They'll want a better draft position.

It's especially important this year because they're not playing next year. That means there won't be a draft, so the 2023 draft should be especially deep.

Not a fan of tanking, really in any sport. We play to win the games.

Ski U Mah Gopher

Member of the Tribe

- Joined

- Nov 12, 2008

- Messages

- 8,177

- Reaction score

- 1,518

- Points

- 113

Plus it's fun playing the spoiler.Not a fan of tanking, really in any sport. We play to win the games.

Unfortunately, this season it looks like the White Sox are running away with the division, and we don't play them anymore after this week.

We will have more to say about the East, though. We host the Rays for 3 & the Blue Jays for 4, and are at the top 4 in the east (4 @ NYY, 3 each @ Boston, Tampa & Toronto).

We also host the Brewers (who are in the thick of the best overall in the NL race) for 3.

TruthSeeker

Well-known member

- Joined

- Nov 8, 2014

- Messages

- 7,911

- Reaction score

- 4,585

- Points

- 113

Shortsighted. What's best medium and long-term is more important than short-term gratification.Not a fan of tanking, really in any sport. We play to win the games.

Losing now in a miserable, under .500 season, increases odds of getting above .500 in future season more quickly.

Attendance and viewership won't increase this season in a lost season, but it could rebound more quickly by losing a few morw games than otherwise this year.

This team also isn't going to be what the new, winning teams of the future will look like in terms of players on the field, so there's no reason to "learn how to win" with the young kids either.

Even if they don't play, I believe there would still be a draft. Where have you seen otherwise?It's especially important this year because they're not playing next year. That means there won't be a draft, so the 2023 draft should be especially deep.

This. I cannot fathom why we are wasting AB's on Simmons. He's beyond terrible at the plate. Sure he's above average in the field, but even Punto hit better than this.It’s time. Let Gordon and Polanco take over for the next two months.

Last edited:

In the NFL or NBA maybe. In MLB, unless there's a Bryce Harper/Strasburgh type player coming out, tanking is likely a waste.Shortsighted. What's best medium and long-term is more important than short-term gratification.

Losing now in a miserable, under .500 season, increases odds of getting above .500 in future season more quickly.

Attendance and viewership won't increase this season in a lost season, but it could rebound more quickly by losing a few morw games than otherwise this year.

This team also isn't going to be what the new, winning teams of the future will look like in terms of players on the field, so there's no reason to "learn how to win" with the young kids either.

And the Twins aren't going to finish any higher than 5th or 6th even if they tank. They are 7 or more games ahead of Texas, Baltimore, Pittsburgh and Arizona and within a game of KC and Florida. The difference between the 5th and 8th picks in baseball isn't worth much. There's a decent chance you take the same player regardless and there's a 50% chance they never see the majors either way.

He played there the last two years. He was below average but not a disaster. There's no team that would start Simmons over him if it were a binary choice. Either go with Polanco/Arreaz or let Gordon have a shot at it.We already know the answer. Polanco cannot play SS. He's a 2B.

TruthSeeker

Well-known member

- Joined

- Nov 8, 2014

- Messages

- 7,911

- Reaction score

- 4,585

- Points

- 113

Exactly, not good. We want good. He's not going to get better with age either.He played there the last two years. He was below average but not a disaster. There's no team that would start Simmons over him if it were a binary choice. Either go with Polanco/Arreaz or let Gordon have a shot at it.

Our long-term SS is either injured or recently acquired. There will another stopgap at SS the next year baseball is played.

GopherWeatherGuy

Well-known member

- Joined

- Oct 24, 2013

- Messages

- 17,862

- Reaction score

- 18,075

- Points

- 113

Might as well get 5th. They'll want a better draft position.

It's especially important this year because they're not playing next year. That means there won't be a draft, so the 2023 draft should be especially deep.

Their lineup will be more than capable of competing next year. It just depends on what they do with the pitching staff between now and then.

Ope3

Sailor Sam

- Joined

- Dec 12, 2008

- Messages

- 13,783

- Reaction score

- 10,604

- Points

- 113

Even as is, it's highly unlikely that they would sink to the level that they would be the #1 pick.Shortsighted. What's best medium and long-term is more important than short-term gratification.

Losing now in a miserable, under .500 season, increases odds of getting above .500 in future season more quickly.

Attendance and viewership won't increase this season in a lost season, but it could rebound more quickly by losing a few morw games than otherwise this year.

This team also isn't going to be what the new, winning teams of the future will look like in terms of players on the field, so there's no reason to "learn how to win" with the young kids either.

Moving up just a few draft spots by "losing a few more games" hardly moves the needle in terms of odds in hitting big on whatever player they select.

With all the shifting, I'm willing to trade a little defensive range for Polanco/Arreaz's bats. Defense isn't as valuable as it was before, IMO. I agree he's probably not the SS long-term. But I see no reason he can't play there next year until Lewis or the Toronto guy are are ready.Exactly, not good. We want good. He's not going to get better with age either.

Our long-term SS is either injured or recently acquired. There will another stopgap at SS the next year baseball is played.

GophersInIowa

Well-known member

- Joined

- Nov 21, 2008

- Messages

- 46,915

- Reaction score

- 31,433

- Points

- 113

Moran is a left-handed reliever that has been lights out this year.

From the Parkinglot

Well-known member

- Joined

- Feb 6, 2011

- Messages

- 6,873

- Reaction score

- 4,014

- Points

- 113

Maybe Austodio can transition from platoon player to an opener for the twins. He can’t be any worse than this kid they trotted out today.