by: Daniel House (@DanielHouseNFL)

Calling an effective football game is like constructing a symphony. It’s important to use different tempos, concepts and formations to keep a defense on its heels. In music, composers introduce a melody and attempt to build off of it. Whether it’s adding in a new note or chord structure, the goal is to keep a listener intrigued. A symphony is complex, but the conductor always wants to tell a story.

Offensive coordinators face a similar task. There is an overarching theme of an offense and the goal is to evolve and add certain wrinkles to it. Coaches understand the personnel they have and design plays to maximize athletic potential. However, during the course of games, the offensive “conductor” has to be nimble and ready to make adjustments. Each week, the goal is to create a new “song” better than last week’s.

Throughout the game, Minnesota offensive coordinator Kirk Ciarrocca made several small tweaks as he constructed his Week 4 RPO symphony.

Each week, the overall concepts continue to change and bye week adjustments helped contribute to this week’s song. It’s pretty clear the offense is continuing to evolve, which is the goal of football and classical music conductors alike.

A Look at Morgan’s Performance and the RPO looks

The tide is shifting for the Gophers’ offense. A group traditionally built upon running the football is creating an explosive passing attack. With the ability to hurt teams through the air, Minnesota is becoming more balanced and multi-dimensional. This year, we are already starting to notice the coaching staff’s ability to recruit and develop explosive wide receivers. During Saturday’s 38-31 win over Purdue, the passing game fueled three scoring plays of more than 40 yards. Quarterback Tanner Morgan was very efficient and set the Big Ten record for completion percentage (95.5%- minimum 15 attempts) in a single game, according to BTN stats. When watching the game back, it’s easy to see Morgan’s comfort with the system. There were a couple instances where Morgan looked off a safety or used a pump-fake to set up a big play. A life-long dream of mine is to have access to college football All-22. However, the television angles were actually pretty impressive this week.

To illustrate the processing skills of Morgan and his ability to understand coverages, I pulled out an example. In pre-snap it looks like he’s going to have two-deep safeties. The free safety cheats down into the box and swivels back to disguise the coverage. He was trying to jump the slant and it left the strong safety 1-on-1 with Tyler Johnson. He put a double move on the strong safety and got separation. Morgan attacked the seam and had 1-on-1 matchups across the board due to the success rate of RPO slants. In this game, he did an excellent job of executing and reading the defense.

What you don’t see from the first angle is how Morgan set this up. As the safety is cheating into the box, he pump-fakes and you can see the safety shift to cover the slant.

This left Johnson in a man situation against the safety. Minnesota occasionally attacked the seam because Purdue was sitting so hard on the inside routes. This was the perfect strategy to take advantage of a single-high safety and so much underneath attention. The Boilermakers were shifting pre-snap coverage looks (often between Cover-1 and Cover-2), but Minnesota always seemed to catch them in favorable single-high matchups. Kirk Ciarrocca continued to modify and tweak the intermediate/vertical concepts. It was like a symphony composer adding a new chord progression in the middle of a song.

An example of this occurred during Chris Autman-Bell’s 70-yard touchdown reception. Offensive coordinator Kirk Ciarrocca dialed up a slant bubble RPO and got the man coverage matchups he was looking for. Like the example above, it looks like (hard to tell from angle) Purdue made another pre-snap switch (two deep safeties to single-high). After running a slant out of this play so frequently, the defense anticipated Bateman would snap off the slant. Instead, he moves to the sideline for a bubble, Autman-Bell annihilates his man, the single-high safety is too far up the hash, and the rest is history. This is an example of capitalizing upon a tendency by adding a very small wrinkle to a successful play.

On Rashod Bateman’s 45-yard touchdown reception, the Gophers again had man coverage across the board. This time, Bateman ran the slant out of the slot, instead of the bubble. Bateman attacked the strong safety (who is playing single-high) and popped off another slant.

The middle of the field was wide-open, and until the second half, Purdue didn’t really make an adjustment to cover underneath. When they started to do that, Minnesota exploited them over the top.

This is the final part of the RPO symphony. One simple play was modified a little to create the third and final movement of the “song.”

Again, the Gophers had another single-high look to attack. The free safety creeps down into the box and the linebackers dropped to cover the deep middle. Purdue’s strong safety is all the way over on the opposite hash and man-to-man coverage occurs for Bateman and Tyler Johnson. With the cornerback’s inside leverage on Rashod Bateman, he runs a sluggo. He stresses the defensive back inside, executes the double move and burns the defense over the top. This was the final wrinkle where offensive coordinator Kirk Ciarrocca built off the core RPO slant play.

In addition to the Gophers’ passing concepts, the rushing scheme evolved. The Gophers mixed in more outside zone and stretch plays to take advantage of running back Rodney Smith’s vision, patience and elusiveness. Minnesota also occasionally inserted redshirt sophomore John Michael Schmitz at center. He fits the system really well, is physical and can execute the reach blocks necessary to run outside zone. I pulled out one example of the Gophers’ blocking scheme variation.

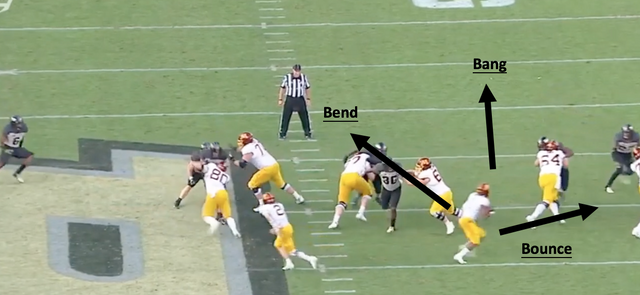

On the above play, Conner Olson sees his man is reacting/moving to the outside, so he keeps driving him up field. He doesn’t even need to reach him because the leverage of the tackle is taking him to the sideline. John Michael-Schmitz does a nice job of shouldering the defensive tackle and reaching him. During this type of outside zone play, a running back has three main options: to bend to the backside, bang (hit the hole), or bounce outside.

In this case, Rodney notices Conner Olson is owning his man and the strong safety is cheating. Everyone is reacting to the outside running play. Smith bangs inside, rather than bouncing. These type of plays allow Rodney to find cutback lanes and use his vision to create explosive plays. With the blend of inside/outside zone, stretch plays and jet-action, the Gophers are adding some variety to the offense.

Minnesota’s passing attack is helping soften up the running game, too. During Rashod Bateman’s sluggo touchdown, eight players were in the box. If a defensive coordinator does this, they subject themselves to getting beat over the top. When you need to help in coverage, the running game will face lighter boxes, which helps the numbers game up front. It’s really tough for opposing coordinators to scheme against this offense because they can beat you by playing a variety of different styles. On Saturday, Purdue was clearly committed to not getting beat on the ground.

A Look at the Analytics

Others areas of Minnesota’s offensive improvement are supported by analytics. First off, advanced metrics really like this offense and hint at the potential of offensive sustainability. Sure, it’s early, but there are a few data points that correlate to success.

The “expected points added” metric (EPA or PPA) helps us shift away from truly evaluating a team solely off yardage. Before every play, an expected points value is provided based upon the down-and-distance. This formula gives more weight and value to plays that result in first downs or positive yardage. For example, the statistic doesn’t place as much value upon a play where the quarterback throws four yards short of the sticks on 3rd-and-10. Expected Points Added factors in down-and-distance to determine success. Field position also plays a role in the value of certain plays and it’s included in the equation. For a simplified version of how this works, I recommend checking out this visual example.

By using expected points added, we can better assess the overall impact of certain units within a football team. The statistic also better accounts for situations in games, such as negative plays, field position and turnovers.

First, Minnesota’s passing game ranks fifth nationally in expected points added (EPA). Only Oklahoma (0.88), Alabama (0.77), Air Force (0.73) and LSU (0.69) are ranked ahead of Minnesota (0.66), according to the CollegeFootballData website.

This means that Minnesota’s passing game is a major contributing factor to the team’s overall margin of victory. The Gophers are converting in a variety of different situations and creating explosive plays. More importantly, they don’t have many negative passing plays or turnovers that bring down the overall expected points added of a certain play.

For example, the output for Minnesota’s rushing offense is 0.059, which ranks 93rd nationally among 130 eligible teams. There have been far more negative rushing plays, which impacts the EPA. When looking at each game’s individual output, Minnesota’s Expected Points Added through rushing has remained relatively constant.

It will be interesting to see how this shifts as the running game improves. We are noticing gradual improvement every week, so the overall offensive outputs could improve. The passing game and running concepts complement each other, so an improvement on the ground can actually open up more play-action looks. As the running game improves, it will be worth tracking this metric to evaluate which areas are contributing to the team’s success.

First-Down Offense by the Numbers

Finally, one of the last areas worth highlighting is the team’s first-down offense. Expected Points Added is also calculated for each down. As I noted in one of my recent posts, during the first three games, Minnesota ran the ball on 77.9 percent of their total offensive snaps. They also averaged just 3.75 yards per play on first-down. During Saturday’s win, they flipped the script and had a 50% run-pass rate. In those situations, quarterback Tanner Morgan completed 12 of his 13 passes for 268 yards and two touchdowns. When running the ball, Minnesota averaged 3.3 yards per carry.

As a whole, the Gophers’ average yards per play jumped from 3.75 to 11.96. With more balance and explosive passing plays, the overall offensive efficiency and expected points added increased. The data shows us that Minnesota’s success on third-down has been the most valuable component to its success.

Minnesota’s Expected Points Added by Down – Offense – (Nationally), per CollegeFootballData:

First-down: (96th): -0.004779

Second-down: (23rd): 0.339081

Third-down: (8th): 0.85512081

Here is the First-Down Expected Points Added for each individual game, per CollegeFootballData:

South Dakota State: -0.016

Fresno State: -0.23

Georgia Southern: -0.16

Purdue: 0.47

Minnesota improved its early down success, which also creates improved play-calling flexibility on second and third-down.

The analytics tell us the Gophers have the ability to control games through the air. This is something that hasn’t happened in quite some time at Minnesota. Now, it will be worth monitoring how the offense evolves when the running game becomes more dynamic.

credit: ESPN for video (intended for fair use) and CollegeFootballData.com for the raw analytics